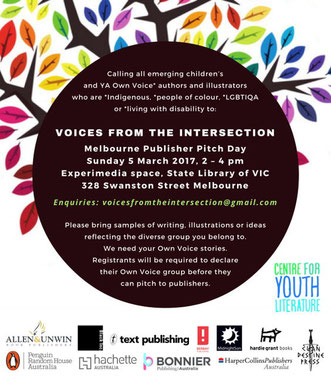

Voices from the Intersection pitching opportunity for YA authors!

My friend Rebecca Lim is the brainchild of this wonderful opportunity for authors with diverse voices to pitch their ideas to a whole spectrum of publishers (listed in the flyer!)

The idea is that we need more YA books that depict different life experiences and perspectives - so if you are a writer of YA books, or an emerging writer, this is your opportunity!

For all enquiries please email voicesfromtheintersection@gmail.com.

Using your voice

I am not particularly good with writing clear-cut opinion pieces, because I find that my opinions are never so clear-cut when I examine them closely. In my twenties, I used to think that writing should hone in on issues, like a torchlight in the dark. But realistically, I personally never quite liked reading those pieces that were didactic, that had a pre-existing agenda in mind, or an overweening goal to change people’s minds and ideas.

I know that I am are less likely to change people’s minds and preconceived ideas, than I am to change their feelings through my writing. But this has to be done in complete transparency. You can’t be sneaky about it, you can’t amp up the emotive barometer hoping that people will be moved. So for example, I avoid ‘making people feel’ anything for my characters, and I have to write in honesty about my own cowardice.

When feelings change, ideas are more likely to change.

Now I see the role of the writer – especially the novelist – as analogous to the role of cameras in covering a football game. Forgive the metaphor, but my team just won the grand final, and in watching the replay, I realise that the fairest and most objective path to the truth is when several cameras are covering the goalposts at the same time. So the role of my writing now is to have several cameras operating at different angles, at the same time.

Back in 2008, I did a writing residency and lived alongside a poet and Professor named Robert Cording, who taught me this:

“The reader must feel that he/she is making contact with a real human being, not simply with arguments and opinions. If the poem feels like it has sifted and arranged received ideas, then it will fail. The poem has to feel, I think, as if there is a real person struggling with real experiences that will not yield some handy lesson, but nevertheless are not entirely without meaning. The voice that convinces will always be the voice of an individual who the reader experiences as an individual and not as a spokesperson for this or that idea.”

Launch of My First Lesson

On Monday 29 August, 'My First Lesson' was launched at the Melbourne Writers Festival to a completely full theatre at Deakin Edge in Federation Square! I would like to thank everyone who submitted to this competition. It was very tough choosing the stories to go in this anthology.

Because we only had an hour for the launch, we could only choose four readers - even though I would have wanted everyone up there reading because all the stories were so unique and the voices so different. Francis, Olivia, Sarah and Noa did a stellar job, especially at the end when they had to answer questions off the cuff, in front of 450 people, with no preparation!

Afterwards, I met many of the young writers, and all of the contributors who flew in from interstate and their families.They were all as delightful, interesting and lovely as I thought they would be. To the contributors I haven't met and thanked in person - I hope we will one day meet, so I can tell you how much I liked your writing. We discovered that Readings Monthly (a magazine in the Age Newspaper) had a review of the anthology, written by Leanne Hall, who is an established, wonderful Australian YA writer herself. You can read Leanne's excellent review here: http://www.readings.com.au/products/21933971/my-first-lesson-stories-inspired-by-laurinda

I am so proud of this anthology, and grateful to my publishers at Black Inc, and thankful that the proceeds will go to Room to Read to fund literacy for girls around the world. Most of all, I am so proud of the young authors who came from every kind of background, school, age, year level and gender, who decided to share their stories with me, and the world. The future of YA is a bright one, filled with diversity of genre and voice, a strong sense of social justice and philosophy, and a deep sense of emotional honesty. What an inspiring launch!

The Other Side of the World

Every once in a while I receive a piece of mail from a reader that is a story in itself, written with such clarity of prose and insight, that it warrants a wider readership.

This young reader from the other side of the world, as you can see, is going to be an author in her own right. In fact, I hope she ends up in charge of her country one day. Her letter taught me so much I thought I already knew about class, culture and belonging. I share it with you, respecting her request that she remain anonymous:

"Dear Alice,

I’m 18 years old, and I just finished reading the advanced reader’s copy of your novel Lucy and Linh, the American publication of Laurinda.

I wanted to send you a message hoping to tell you that I don’t think I’ve resonated or identified with a character more than Linh for a very, very long time – while I’m white, I’ve been brought

up living below the poverty line, while simultaneously living in a town known for its wealth upper/upper middle class families. In other words, I lived in literally the only ghetto in town,

surrounded by a bunch of giant sparkling houses on the beach. I live in a lower middle class neighborhood now, but spent around 10 years in poverty with my dad.

I gravitated towards Lucy and Linh because, in a little less than two weeks, I’ll be going off to a good University with about $16,800 a year of scholarship money earned through, almost eerily

similar to Linh, a standardized test grade with a perfect writing score (and some financial aid).

Never have I read something that accurately portrayed and translated my feelings into words growing up this way. Never have I ever read a story about a character living in poverty that wasn’t

used as a poster child for the needy, or a sob story to make kids feel bad and humanize the poor people in their schools and towns. When I was Linh’s age, I remember writing countless poems and

stories and songs about how much I hated living where I did, struggling like I did, and the anger I felt receiving pity from my rich friends whenever they came over to the grungy trailer my dad

and I lived in; the one that had stray cats living under it and bugs in the walls and dips in the floors and ceilings – meanwhile their houses had three stories, pools, flat screen tvs,

wood floors, and parents that threw money away like it was nothing.

I’ve never read a story with a character that accurately expressed my same shame and jealousy, but also more importantly my same sense of pride in myself; my love for my dad and my neighborhood

friends, and my knowledge that I was a strong person – not “oh, look at how strong you are to manage to do so much even though you live here” kind of “strong” – but that I knew I had depth,

character, and worth.

That I felt like I was a gem, even if on the outside it seemed like I was a stain when I was surrounded by everyone at my school; or as I watched the towering houses and perfect lawns pass by

before my bus dropped me off at the entrance to my neighborhood, right next to the stinking drainage ditch. I came to realize that I was envious of what they had, but far from envious of who they

were.

I just wanted to thank you for writing and that I hope your books find themselves in the hands of many over here in America next month when Lucy and Linh is published. I’m going to be majoring in

International Studies as well in college, so I hope I can learn about people from all over the globe without being intrusive to their personal lives or culture. The last thing I want to be like

is Mrs. Leslie and her friends, who display the type of racism I’ve noticed that isn’t seen as racism by most white people – the over glorification of only bits and pieces of other cultures (and,

unintentionally but all the same, dehumanizing people by acting as if everything they do is exotic, cool, or trendy, something I feel in the past I have been guilty of myself and makes me cringe

to think about, but I know is important behavior to face, correct, and never revert back to).

It also saddens me to say my father and other family members act like those white people who are so paranoid and afraid of losing what little they have in poverty, that they take their aggression

out on those of color to feel as if they’re not at the bottom of the chain.

It’s a behavior that’s been gnawing at my insides as here in America Trump is glorified by playing at those dark feelings in people’s hearts. I despise it and I think about it constantly, to the

point that I’ve cried in frustration that people can’t even look past the smoke and mirrors to see that they’re fighting the wrong people for crumbs, when the real culprits are at the top with

enough to stuff themselves and their grandchildren for the rest of their lives.

I don’t want to be like either of those kinds of people – be it the angry ones or those that are too invasive. I want to be change.

I want to learn and understand the world past the shallow surface level, expanding and reaching out and making connections with people and loving with all of my heart. I truly love people, and

love genuinely giving love, even in its smallest forms – not giving to boost my self-image or to give myself a pat on the back, but for the mutual feeling that’s almost impossible to describe

when shared with someone.

I just really, really loved your book is what I’m trying to express I guess. I hope that I haven’t wasted your time or made you uncomfortable, but it feels as if I read it at the perfect time in

my life.

I feel as if I can go to my school, in my fancy dorm suite, in my fancy classes, with my fancy roommates, and not lose myself or what I care about – to not forget who I am and where I come from.

That was my biggest fear, but I think that I don’t have to worry about it anymore."

Peril turns 10!

The Linh Enigma

Spoiler Alert: If you have not read Laurinda and intend to, please don’t read this entry as it contains an important spoiler! If you have read the book, this post explains why I used a certain literary device in the construction of my character, Lucy.

The old adage of ‘Be Yourself’ is a cliché and sometimes the least helpful advice you could give someone facing a new situation. Sometimes, instead of clinging doggedly to this fixed sense of self you have, it is better to adapt to your circumstances. Sometimes, you have to be a different person to belong. Not all change means that you are compromising your essential 'self'. When I was a teenager, I read a James Maloney book called Gracie, about an indigenous girl who goes to an exclusive Brisbane Girls’ Boarding School. Gracie thinks the word shit is part of normal daily conversation, has no idea that to certain sectors of society it’s offensive, and only realises this when an adult points it out.

Laurinda is also about a girl, Lucy, who has to adapt to a very different set of rules in an institution with which she has no familiarity. Her friends from her former Catholic school have certain negative assumptions about girls who go to private schools, while her friends at Laurinda Ladies' College also assume certain things about those who live in the Western suburbs of Melbourne. That is why Lucy realises that in order to stay a part of the new school, she has to keep her true self apart.

She begins by changing the name by which her family and former friends knew her - Linh - and adopting the more Anglicised Lucy. So many of my friends have told me stories of how teachers, parents or they themselves changed their names in school to sound less ‘ethnic’, and make it easier for other people to pronounce. In 1996, during One Nation’s burgeoning rise to power, my friends who came here as refugees were ashamed and tried to hide this fact. Some of our parents ingratiated themselves to ‘society’ by becoming more 'patriotic' than the racists, decrying the recent un-Australian boat immigrants as free-loading ‘illegal’s to prove how much they themselves had assimilated, and to differentiate themselves as the ‘good’ migrants. I also started to notice more Asian teenage girls, like the character of Tully, dying their hair blonde and wearing blue eye contacts.

Those who have never been part of a minority race, culture or sexuality or had to live with a disability, may also have never had to develop a ‘status quo’ persona to fit in. They've probably never had to assume a different identity so that they would not stand out and be a target of other’s assumptions. They’ve never had to flick through a magazine and see that ‘beautiful’ people don’t really look like them. They’ve never considered that when we call a sector of society’s tastes and belongings ‘tacky’ - as we do with the things that poor people can afford - we are saying that they will never rise up to our ‘class’ even if they had money.

So my 'letters to Linh' approach was my way of addressing this issue, because essentially and undeniably, Lucy becomes a different person at Laurinda. She has to be polite and carefully watch her diction or - like Maloney’s Gracie - no one will listen to a word she says. She has to be a helpful and patient cultural ambassador in case she alienates the other girls and their parents, cementing their inadvertent racism. She wears pastel ‘designer’ clothes instead of the black garb with gold buttons she likes so much lest her classmates realise she’s bogasian trash.

And yet, she understands that even though these girls will always see ‘Linh’ as some kind of feral ethnic hooligan, those in Stanley knew her as a feisty, funny, kind and spirited girl and are proud of her. So of course she misses her old self but she can’t go back to being exactly that kind of girl. So instead, she writes letters to a self she once knew and admired, hoping that vestiges of Linh will remain with her.

The reality is that this is what it is like for first generation migrant kids whose parents want them to shift class - they also, inevitably, end up moving massive tectonic plates of their culture too.

Class and Culture

On the 17th of November I was on ABC radio discussing culture and class with Jon Faine and Christos Tsiolkas, a writer I admire very much for his unflinching honesty in dealing with suburban

life. Here he is, in the red shirt, so jovial, genuinely warm and cheery in real life. Beside us are two very talented musicians David Bridie and Charles Jenkins.

The audio link to our conversation is below:

http://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2014/11/17/4130163.htm

Laurinda Q & A

Over the past weeks, I have been asked many questions about Laurinda at launches, public talks and over the radio, so I thought I would share these written answers with readers about the book:

How much does Laurinda draw on my own life experiences?

Growing up, I went to five different high schools, and I have always been fascinated by the way institutions shape individuals. In each new high school I felt like I was a slightly different person - not because anything about me had immediately changed - but because people’s perceptions of me had.

High school is the only time in your life where a large part of your identity is actually shaped by other people. As an adult you can choose your friends, and your time is finite, so of course, you try to only spend time with people who like and affirm you. As a teenager, though, you are forced to fit yourself in amongst 200-1000 other people, who are all with you every day. So I’ve always been interested in how teenagers adapt to this.

Many of the examples in the book are taken from direct experience, or experiences of my teacher friends. When my editor was editing Laurinda, he felt that some parts were so far-fetched he asked me whether I could change the examples. I had to let him know that these things actually happened! 15 year old girls can be real pieces of work sometimes. However, Laurinda is a completely fictional school. I created it as a representation of institutions that value success at all human cost.

Lucy Lam, my protagonist

When I wrote the character of Lucy, I was very aware of her voice first and foremost, very certain that the reader would be hearing her thoughts and not her words. She’s what school psychologists would now call a classic introvert, but the fascinating thing is that she was not an introvert at her previous school. It is only coming to Laurinda that she loses her speaking voice.

Lucy’s tenacity is not that she charges into the institution of Laurinda and speaks her mind, but that she silently watches this world unfold to gain understanding of it. Many young adult books stress the importance of belonging to a group, yet Lucy is content to be by herself at school after she recognises that the institution is rotten. When evil exists, we are taught to do something about it - Lucy’s non-participation in the institution is a form of resistance, and I think it’s pretty stoic. You have to have a strong sense of self to choose to be ‘a loner.’

What is the Cabinet?

The Cabinet are a trio of three girls who ‘run’ the school and lord over their long-suffering classmates – and teachers.

In Amber, Chelsea and Brodie, I wanted to create characters that were so entitled that they didn’t even realise how entitled they were. There’s the old cliché of the silver spoon, but I didn’t want these characters’ entitlement to be based on wealth - I wanted it to be based on cultural capital: the handed-down power that exists in our society. Their alumni mothers trained them to appreciate Royal Doulton and institutional loyalty, their fathers are powerful men and their school Laurinda trains them to be ‘Leaders of tomorrow.’

So of course they’re going to want to ‘lead’ the school. They feel it’s their birthright. And also, being such perfectionists, they feel a duty to weed out the weaker elements of the school: vulnerable teachers, students they feel are not up to scratch. I did not want the Cabinet to be vacuous ‘mean girls’, but the sort of pressure-cooker girls you would meet at a private school who must be on top of things all the time; and yet whose worlds are so tightly-wound that any threat to their order would ignite them. And I hope readers come away with an understanding that those girls are as much victims of institutional and familial insularity as they are cruel.

Why did I set Laurinda in the mid 1990s?

I deliberately set the story before there was social media and cyberbullying, for three reasons. The first is that young adult readers are the most discerning and astute audience you’ll ever have. They can tell a false note a mile away, so if I set the book in contemporary times and got cultural references wrong or tried to ‘be with it’ in relation to social media, they would know I was trying way too hard.

Secondly, I wanted the girls to demonstrate their nastiness in person, physically, face to face. There’s a certain kind of courage in this – like how soldiers used to fight wars, bayonet to bayonet. They could not hide behind drones.

Finally, I wanted to cement Lucy’s outsider status so the reader got a real sense of her complete alienation and disconnect from the school. I wanted the reader to hear her uninterrupted reflections on what this meant, to experience her working things out, thought by thought. This could definitely not be achieved if her inner monologue was constantly interrupted by her facebook posts or tweets, which are never representative of a person’s true state of mind anyhow, just symptomatic of temporary feelings.

Why is there a kilt on the cover of my book?

The uniform of the private school was a powerful symbol for me when a student myself. When I got my first kilt ($115 back in 1996!) I felt extremely guilty: neither of my parents had owned any singular item of clothing that cost as much. Also, I watched the way private school kids moved and walked and behaved in their uniforms, and realised that little 6 year old boys in blazers could not ‘play’ or ‘play fight’ without doing at least a hundred bucks damage to their clothes. The blazers were also emblematic of the suits they would wear in the future as men and women of power.

Power in Laurinda

People like to bandy around that cliché that ‘power always corrupts.’ But when I was twenty and a student of politics at university, Aung San Suu Kyi wrote something in her book, Freedom from Fear, that has always stuck with me. She wrote that power doesn’t in itself corrupt. What corrupts is fear – fear of losing that power, fear of being overpowered. So power in itself is neutral.

Race in Laurinda

I deliberately made the ‘race’ related aspect of Laurinda subtle, because that’s how racism works in real life. You are never quite sure whether something is racist or not, unless it’s in your face. Lucy grows up in Stanley where the local residents at the shopping centre are explicitly racist and hateful. They’re afraid of Asians stealing their jobs and hogging government support.

But at Laurinda, which is meant to be more civilised, the girls have not had much exposure to different cultures, so they treat every brown and yellow person like a fascinating perpetual exchange student. They don’t realise that those kids – Lucy, Harshan, Anton, Linh – are teenagers in exactly the same ways they are. They don’t realise that by reducing a person solely to their culture or race is a form of racism. It’s like treating a person with disability as if the only riveting thing about them was their blindness or deafness.

Class in Laurinda

One particular high school I went to was in the working class suburb of Braybrook, and most of the girls there helped at home or worked outside of school. They were also responsible for either looking after sick adults, or at the very least, translating for parents who could not read or write. Many had to fill out their own enrolment and excursion forms. In all senses except legally, they were like adults.

Conversely, I’ve visited countless other girls’ schools where the students are trained to be ‘future leaders’ through debating, public speaking and musical prowess. Yet many of those girls aren’t even allowed to catch a public bus home by themselves. They seem so helpless, which is why I called the trio of mean girls in Laurinda ‘The Cabinet’ – a very showy artefact which belies its conservative domesticity. The girls in the Cabinet may rule over their domain, but their domain is a very insular one.

In Laurinda, I wanted to explore how you could have one group of students who were very ‘worldly’ and political in an academic sense but had no clue outside their leafy suburbs, while another class were real-worldly, but had no chance academically.

Talking Points: Bigotry in Australia Speech - Melbourne Writers Festival 2014

Rotunda in the West - Footscray Launch

Tonight my friend Bruno Lettieri, literary and educational Godfather of the Western suburbs, launched Laurinda at Victoria University, Footscray. It was a very special evening because not only were my mum and dad there, and of course, Nick, but also two dear friends of mine - Les Twentyman and Richard Tregear, the legendary social workers - came along too! It made our conversation about class and educational disadvantage more real.

I feel a real sense of community when I return to Victoria University's Rotunda in the West - so many familiar faces like James Howard the local filmmaker, the local teachers, Michelle Fincke the

journalist - all gathered for an evening with the professional writing and editing students. We had a delicious dinner beforehand cooked by the hospitality students in the VU bar, and I realised

how remarkable it was that a university could so perfectly integrate literature and 'the trades', and honour them both.

Photo of Bruno by Pam Kleemann

Residency Inside a Dog!

Hi everyone,

This month I've have a blogging residency at the State Library of Victoria's YA site, Inside a Dog. You can find the blog here: http://insideadog.com.au/residence.

It is actually quite challenging to blog twice a week, different from keeping a private diary where you can be as insular as you like. But it has been a lot of fun - I wrote about how I write,

why I write, why I love John Marsden, the sort of YA books I love, my first career aspiration and my publishing failure (complete with embarrassing illustrations!).

I'm so excited that my new book Laurinda has come out this month, and grateful for the wonderful feedback from my YA readers! THANKS A MILLION!

Alice :-)

Laurinda launch

ON Wednesday 22nd October the great John Marsden came to Janet Clarke Hall, the university residential college where I've taught, currently work as Artist in Residence and live with my husband

Nick. I walked around in a happy daze for days. To have one of your literary and educational heroes (John's also the principal of Candlebark) launch your book and then to find out that he is

funnier, kinder and more wonderful than you imagined is pretty awesome. Many people came to talk to John afterwards, he made time for them all and even signed their well-worn, well-loved copies

of his books.

You can't see it in this picture, but John was wearing an impressive pair of tracksuit pants with double white stripes down the side. Not only does the man have wisdom, talent and the love of

five million young adult (and adult) readers, but he also has gangsta flair. It was the perfect outfit as Laurinda is set simultaneously in a private all girls' school as well as the

rough Western suburbs of Melbourne.

As an author you spend a lot of time - years - with a book, furiously plugging away at it, getting to know your characters and letting them take you where they want to go, doing edit after edit,

that when it finally is here - you feel like you have to adjust to being out of hibernation. What a great way to come out of hibernation. Thank you, John Marsden.

For those interested, the public events for Laurinda are here, I'd especially love to see teenagers,

teachers and YA lovers there!

Alice

Books change lives

The title of this post sounds like a hyperbole but books actually do change lives in a literal way in the suburbs where I grew up. This is a picture of my friend Richard Tregear, Australia's longest serving youth worker, and one of the kids he looks after, Tahlia, who are both featured here:

Sometimes, you have to labour to write the perfect conclusion to your article. But when I interviewed 16 year old Tahlia, she gave it to me. She said, "I write quotes down in my diary. Do you want to hear the latest one? Okay, here it is: 'It's okay to be a glow stick. Sometimes you've got to break to shine."

This is from a longer article found here.

Occupational Hazards Part 2

When people say ‘I get depressed’, I think about how inaccurate that expression is.

They didn’t go out there to some Mental Ailments Marketplace and say, “Umm, I think I’ll get myself some of that depression, oh, is it two for the price of one day today? Wonderful, throw in some of that anxiety too!”

They did not get depression. Depression got to them, slowly and stealthily, like some creeping assassin. This is the other occupational hazard of being a writer. You spend too long alone with your thoughts and they become your only companions, the sort of friends who repeat the same old tedious tales, the sort who you only tolerate because you’re stuck with them.

Most writers deal with these unwelcome visitors, these tenacious mental intrusions. Sonya Hartnett’s work would not have its exquisite melancholy without her understanding of the condition. The great John Marsden would have never been able to create such deep, stoic teenagers. I read a touching interview with John Green – funny, witty John Green – who worried that his depression might impact not on his writing, but on impending fatherhood.

What I think is happening as writers is that we are using our senses all the time, at such a high frequency, that eventually and naturally, our edges blunt. Your sight, touch, taste, smell and hearing need a chance to recover, or they become numb. In Buddhism there is a sixth sense, the mind, which ties all your other senses together. If you keep agitating your mind – which is essentially, what writing is all about – and never give it rest, then of course it’s going to break down. This is not unnatural. You’ve just got to lay the tool down and rest.

Those unwelcome bleak visitors eventually leave if you let them. If you keep paying them more attention than they’re worth they’ll bring friends and gate-crash. But if you are patient and stop listening to well-intentioned people who offer unsolicited clichés of positive-thinking, it will pass. (I think people who are hell-bent on positive-thinking as a cure-all have an unhealthy relationship to suffering: they cannot stand to see it at all costs. This speaks more to their lack of empathy than to your ability to cope.) You can be down, and still have the insight to hope.

Anyhow, eventually hue by hue, sound by sound, taste by taste, feeling by feeling, the world comes seeping back in all its technicolour glory. And oh, what a miracle it is – you see everything as if you’ve ever seen it before. You look at a school mug on your table and wonder who designed its perfect shape and logo, you feel gratitude for the teacher who gave it to you from the public school who woke up at 6am to bake brownies for your visit. You listen to music and feel like the 12 year old Michael Jackson is in your living room. You look at your husband and feel so grateful that he is so constant and calm, and you know that you do not need to share your pain for it to be halved. You hear a dog bark outside and it makes your heart roar with thankfulness.

The ordinary becomes extraordinary again, and you are back to writing.

Occupational Hazards

When she was 19, my Burmese friend Khet wrote a story about a girl contemplatively gazing out an open window which had bars covering the window. Many houses in Burma had such windows, but the military junta thought she was criticising them (screen = bars = lack of freedom). They arrested her, threw her in jail, tortured her, and then put her on death row. One by one, she saw her friends go.

Eventually, she was released, but for the rest of her education, a member of the military would follow her everywhere, every day. Even now, for the rest of her life, there are military people tracking her family in Burma. She still writes, and lives in the USA now, where she has been granted asylum.

Her story is here:

http://www.sampsoniaway.org/literary-voices/2010/08/12/fighting-with-writing-political-activism-and-social-work/

Comparatively, we have it lucky in Australia. The worst that could happen here is probably people who disagree with you stop buying your books and write nasty internet things about you.

If you choose writing as a profession - and it is a choice in Australia - one of the best things you can do is to NOT get carried away with the hype about how brave it is to put a pen to paper. What really matters in writing is using all your five senses - tough, sight, smell, taste, hearing - and to use them fully you have to experience your world fully. Not just the world of writers, but the world of cleaners with three children, cab drivers who were once scientists, garbage collectors, oncologists, your drooling uncle Keith who can't get over the fact that back in the 1950s his football team lost a premiership.

The irony is that what makes you smaller is what helps you grow as a writer. You might need confidence in other areas of life, but you do NOT need confidence to write. When I've felt particularly faithless in myself, I go out into the streets and interview people or friends and write their stories. It has taught me that writing is not about me. It's about the story. Having too much confidence is actually bad for an investigative reporting piece, because you assert your own voice and assumptions over the narrative. Doubt has been one of my greatest tools, because it leads me to explore all possible channels of a story, and I don't start with preconceived ideas.

The other, very important thing about having a writing career is that you MUST have financial independence. I have never been a full time writer, ever. Having another job to go to - even if it's part time, even if its at Safeway - gets you out into the world, makes you a witness to life around you. It spares you from depression and stagnation and guilt and poverty. Because the truth is, as a writer you are not going to be writing 8 hours a day, five days a week. You will not be inspired all the time. Think about how hard it is to write a 800 word creative writing piece for school assessment where every word matters. Now, think about doing that full-time, every day, for your adult life and that's all you do. Try it for a week and you'll see how very, very few people actually write full time. But break up that week with school, and sports, and other things and it becomes more tolerable, even fun, even something you can't wait to get back to doing. It's no different as an adult - get a job, exercise, be curious about other people. When your writing time is finite, you will never get writer's block because you will make the most of it.

Why I write - June, 2014

Writing is not something I do full-time. I also work as a legal researcher in the area of minimum wages. Writers can sometimes be too fixated with ideas, and where there is fixation there’s also ego, a sense that you created that. And then also a corresponding sense of failure if people discredit your creation. But my day job keeps me responsible and answerable to other people. It takes me outside of myself and my introversion and obsessions.

When I was seventeen, I was very unwell, sitting on the floor of our family room at home, curled up like the drab and flimsy shell of a snail. I’d lost all my words because I’d had a nervous breakdown, which had been creeping up at me like a malevolent black shadow for some time during the last ten weeks of my final year at school. I literally lost all my words. Reading the newspaper, the print would swarm in front of my eyes. I could pick out each word but they made no sense. I was as responsive to the outside world as a television screen, switched off.

Anyhow, so that late morning, I was sitting on the floor, probably looking at my English exam notes. I did not have an epiphany. All that happened was my mother came in and said, “Do you realize what time it is? Don’t you have an exam in half an hour?!” My mother – who cannot read or write in English herself, and can barely write in her first language – sped me to the school and I took my first exam.

I sat in that exam room, and despite not being able to write or read for weeks on end, not even feeling up to speaking, I forced myself to write for three hours. To this day I have no idea what I wrote about. It all seemed like gibberish. Then the next day, I did it again. I did it four more times, because all my subjects in Year 12 were humanities subjects like history, literature, politics, legal studies.

I did okay in those exams, though. Well enough to get me into law school, where I learned that the people who had the words were also – not coincidentally – the people who had power in society. I also know that I grew up with a mother whose only literature is the Safeway and Target advertisements in our mailbox every week.

Sometimes you write because you can. Your circumstances allow you to. Sometimes you write because you have to. You might need the money. Sometimes you write because you are forced to, because to keep whatever it is you have inside may mean that you will implode.

There is no one solitary reason. But you should never take your writing for granted, never feel like you own it or that it owns you. There is a book by Lewis Hyde called The Gift (given to me as a gift by my wonderful friend Professor Ronald Sharp) which is about how all art is a gift – that inspiration, or talent is a gift, a culmination of all the ideas and acts and events you have experienced, read or witnessed – and that you have not done it all alone.

I learned a lot about writing at university through reading widely. But always in my heart I loved young adult books and kept returning to the ones I knew as a young adult myself. One of my favorite authors when I was growing up was a gentle man named Robert Cormier, who lived in the same town all his life, and wrote for the local paper. He also wrote some of the best young adult books the English speaking world has come to know: The Chocolate War, Fade, I am the Cheese, We All Fall Down. I also loved Cynthia Voight. These authors had real character driven books, and their characters did not always find resolution at the end.

Writing also takes time. Her Father’s Daughter took a decade. Unpolished Gem took five. Some exuberant people who are good at talking always reckon that they could just sit down and write a book one day, but that they are just too busy or just don’t have the patience. I admire their confidence and their optimism, but I wonder if they realize that writing words is the opposite of saying words. It’s not words that you are putting down on a page, but thoughts. Many writers write because they have sat alone for as long as it takes, to get out what they have to, because they cannot say such things in real life. Such things are impolite, radical, offensive. Such writers don’t have the same voices in ‘real life.’ We are the people who listen (the skill of writing is not talking but listening) and we watch.

Writers affirm people’s best selves back to them – and by best selves, I do not mean most well behaved selves, but the selves that are vulnerable, difficult to love, engage in stupid acts and small transgressions – your best self is your human self. It is your human self that makes the reader feel like they are not alone in their petty selfishness, uncertainty, envy, irrational anger, judgment. Your human self is the self that, upon discovering love as a verb and not an adjective, finds love hard work all of a sudden, but do it anyway. Your best characters have integrity - which simply means that you’ve managed to integrate all the parts of them, both good and bad.

Finally, people often ask me if my family has changed since the publication of my books (since my first two books were about them). Of course my family has changed, like every family. But not as a result of my books, which my mother still can’t read. Books don’t change people. People change people. Acts of love change people. I would like to think that my books were books of love, and I am lucky to have a family who has accepted them as such.